Communism, particularly in its Marxist and Maoist variants, profoundly influenced the Western intellectual tradition beginning in the late 19th century. One shocking report reveals:

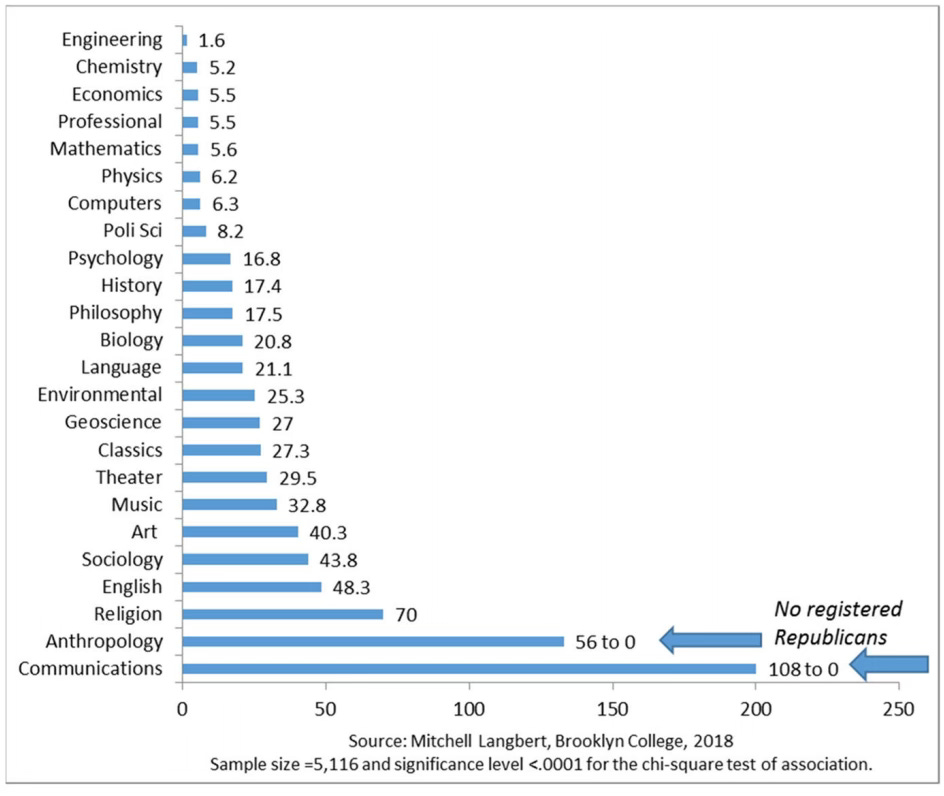

10 Democrat professors for every one Republican professor overall.

70 Liberals for every 1 Conservative in religion departments.

39% of these institutions have ZERO Republicans.

(Helpful research notes for your knowledge and personal research below)

The ideology of grievance, death, and cultish control found its way into the broader Western society in the 20th century through various channels, including academic institutions, labor movements, and political organizations where the dark anti-human doctrines were contoured to be hidden in plain sight within American ideals. The result has been a national indoctrination and a potentially incurable poisoning of the Western intellectual tradition.

In 2018, Mitchell Langbert, an associate professor of business management at Brooklyn College, conducted a revealing study of the political landscape of faculty at America's top liberal arts colleges that was reported by the National Association of Scholars. Langbert examined the voter registration data of 8,688 tenure-track, Ph.D.-holding professors across 51 elite institutions which uncovered a stark ideological imbalance: Liberals overwhelmingly outnumber Conservatives among those responsible for preparing the next generation to lead the nation.

Langbert's findings raise critical concerns about the implications of such political homogeneity on academic integrity, research quality, and the broader intellectual diversity necessary for a robust educational environment.

Critical Pedagogy

The Frankfurt School's emphasis on critiquing culture and ideology led to the development of critical pedagogy. Scholars like Paulo Freire, adapted Marxist ideas to advocate for education as a tool for social change, emphasizing the need for critical consciousness among students to challenge oppressive structures.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Maoist ideas influenced radical pedagogy, particularly in the context of student movements and educational reform. Mao's emphasis on the importance of education in revolution inspired educators and activists to adopt more radical approaches to teaching and learning, often focusing on empowering marginalized groups and challenging traditional authority.

Listen to this teacher at speaking Harris-Walz rally proudly proclaim that education is not about teaching but rather “The greatest instrument of social justice in this country”

The Frankfurt School intellectuals combined Marxist theory with psychoanalysis, philosophy, and sociology to critique modern capitalist societies. Their work, particularly on ideology, culture, and authority, deeply influenced American academia, especially after many members of the Frankfurt School fled to the United States during World War II.

Over the last half-century, an overwhelming dominance of Leftist faculty has taken over academia. Professional activism as a model of indoctrination has replaced higher education and training presenting a grave threat to the American Republic. As this phenomenon has progressed over the decades, traditional Democratic political notions have been overtaken by openly Marxist-Maoist ideology.

Democrats Outnumber Republicans 70 to 1 in College Religion Departments, 10 to 1 Overall

Key Points from Langbert’s study:

Staggering Imbalance, Political Homogeneity, and Bias:

Among 8,688 full-time Ph.D.-holding professors in 51 top-ranked liberal arts colleges, there exists a Democratic-to-Republican (D:R) ratio of 10.4:1. This ratio becomes even more pronounced (12.7:1) when excluding military academies like West Point and Annapolis. Remarkably, nearly 39% of the colleges surveyed had no Republican faculty members at all.

Worst Disparities in Specific Fields:

The imbalance is most severe in departments such as anthropology, communications, sociology, and English, where not a single Republican faculty member was found to counterbalance the overwhelming Democratic majority. Even fields like biology and environmental science, typically seen as more scientifically grounded, exhibit significant Democratic dominance, potentially due to the influence of ideologies like evolution and climate change orthodoxy. The ratios are most extreme in religion departments where Liberals outnumber Republicans by as much as 70 to 1.

Impact of Political Bias on Research and Teaching:

Such a one-sized atmosphere results in biased research and teaching, particularly in fields like social psychology and gender studies, where left-leaning ideological assumptions dominate. This bias not only compromises academic credibility but also creates an environment where conservative viewpoints, particularly those of evangelical Christians and other traditional religious groups, are marginalized or misunderstood.

What do they teach?

Exceptions to the Rule:

A few institutions, such as Thomas Aquinas College, where all faculty are Republicans, and the military academies, demonstrate that political diversity is achievable when institutions foster supportive environments. These outliers suggest that institutional factors play a significant role in shaping the political landscape of faculty.

Institutional and Regional Factors:

Langbert’s analysis highlights that colleges in more Democratic-leaning states, particularly in New England, are more likely to have a higher proportion of Democratic faculty. Conversely, colleges in Republican-leaning states, or those with a tradition of emphasizing interdisciplinary teaching and downplaying the publish-or-perish culture, exhibit more balanced political affiliations.

Implications for Policy and Reform:

Given the entrenched nature of this bias, Langbert suggests that reforming existing colleges might be an insurmountable challenge. Instead, he advocates for the establishment of new institutions from the ground up, designed to foster genuine viewpoint diversity and provide a balanced educational experience.

The stark political imbalance within elite liberal arts colleges, particularly in fields related to religion, highlights a broader problem within American higher education. This bias not only undermines academic integrity but also leaves future leaders ill-equipped to understand and engage with conservative and religious perspectives. The solution may lie not in attempting to reform these deeply biased institutions but in creating new ones that prioritize intellectual diversity and balance.

Beautiful Trouble: Website promoting Marxist-Maoist tactics for American students

The Adaptation of Communism to Western Values (Research Notes)

The influence of Marxism on Western intellectual traditions began in the late 19th century but gained significant momentum in the 20th century. Marxist ideas were disseminated through various channels, including the academic institutions, labor movements, and political organizations.

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 provided a model that inspired many Western intellectuals, who saw it as a successful implementation of Marxist theory. The American Communist Party would be formed shortly after the Bolshevik Revolution and before the Chinese Communist Party.

The establishment of the Soviet Union under Vladimir Lenin, followed by Joseph Stalin, offered a concrete example of Marxism in action, which attracted attention and admiration from some quarters in the West.

Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) was an Italian Marxist theorist whose work significantly impacted Western intellectual circles. Gramsci's concept of cultural hegemony proposed that the ruling class maintains power not only through political and economic control but also by shaping cultural norms and values.

This idea became influential in Western academia, particularly in the fields of sociology, political science, and cultural studies, as it offered a framework for understanding how power operates in societies.

The Frankfurt School, a group of scholars and Marxist intellectuals associated with the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt, Germany founded in 1923, was a research organization at Goethe University that played a crucial role in the development of Western Marxism through the development of Critical Theory.

Critical Theory is a philosophical and social movement that critiques and seeks to change society by analyzing the power structures, ideologies, and social practices that maintain and perpetuate power structures and systems of inequality.

Critical Theory has influenced various fields, including sociology, cultural studies, literary theory, education, and political theory. It has also informed social movements focused on social justice, feminism, environmentalism, and other forms of resistance to oppression.

Overall, Critical Theory is described by its advocates as both a theoretical framework and a practical approach for understanding and challenging the social forces that perpetuate inequality and hinder human freedom.

Journal Report, October 1990: Research article: Are We Losing Our Liberal Arts Colleges? by David W. Breneman

Maoism's Influence on the West

While Marxism had already established itself in Western intellectual circles, Maoism introduced new ideas and strategies that resonated with certain segments of the Left, particularly during the 1960s and 1970s.

Herbert Marcuse (1898-1979), one of the most prominent voices in American academia, integrated elements of Maoism into his critique of Western capitalism. Marcuse's concept of "repressive tolerance" argued that liberal democracies tolerate dissent only to a degree that it does not threaten the status quo.

The radical student movements of the 1960s in the United States saw Maoism as a more radical alternative to conventional Marxist strategies and found Marcuse’s critique especially useful.

The Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which initially focused on civil rights and opposition to the Vietnam War, increasingly adopted Maoist rhetoric and strategies, including a focus on revolution and the necessity of violent struggle.

The influence of Mao's Little Red Book and the Cultural Revolution in China inspired segments of the New Left in America to embrace more militant and revolutionary approaches.

Communism's adaptation to Western values occurred through several mechanisms, including the blending of Marxist ideas with cultural and social issues specific to Western societies. Unlike the Soviet Union or Maoist China, where Marxism was implemented through state power, in the West, Marxism and Maoism were often adapted to fit into existing cultural and intellectual frameworks.

The American Blend: Cultural Marxism

Cultural Marxism describes the influence and application of Marxist theory to cultural and social issues in Western culture, including race, gender, and identity. Rather than focusing solely on the proletariat's economic struggle, Western Marxists adapted Communism to address the specific grievances and social dynamics within Western societies.

Critical Theorists adapted Marxism to Western contexts where culture, rather than class struggle, became the primary battleground. This approach profoundly influenced academic disciplines such as sociology, cultural studies, and literary theory, where Marxist ideas were applied to critique Western culture.

Postmodernism and Neo-Marxism

In the latter half of the 20th century, postmodern thinkers like Michel Foucault and Jean-François Lyotard incorporated Marxist ideas into their critiques of power, knowledge, and discourse. While not Marxists in the traditional sense, these thinkers borrowed from Marxist analysis to develop new ways of understanding the complexities of power in modern societies. This fusion of postmodernism and Marxism, often termed Neo-Marxism, further adapted Communism to Western intellectual traditions by focusing on issues like identity, power relations, and social justice.

Impact on Academia

The influence of Marxism and Maoism on Western academia cannot be overstated. These ideologies provided the foundation for much of the critical scholarship in the humanities and social sciences during the 20th century.

Gramsci's idea of cultural hegemony became a central concept in academic discussions about power and society. His work influenced various fields, including political science, cultural studies, and education, where scholars explored how dominant ideologies shape social institutions and cultural practices.

Civil Rights Movement

Marxist ideas, particularly those related to class struggle and oppression, found resonance in the American Civil Rights Movement. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X incorporated elements of Marxist analysis into their critiques of racism and economic inequality. While not explicitly Marxist, their emphasis on systemic injustice and the need for radical social change reflected the broader influence of Marxist thought.

Countercultural Movements

The countercultural movements of the 1960s and 1970s, including the anti-war, feminist, and environmental movements, were significantly influenced by Marxist and Maoist ideas. These movements often framed their struggles in terms of a broader critique of capitalist society, borrowing from Marxist analysis to articulate their demands for social and political change.

Identity Politics

Identity politics emerged in the 1960s and 1970s as various social movements began to focus on the specific experiences and struggles of marginalized groups based on race, gender, sexuality, and other identities. While traditional Marxism emphasized class as the primary axis of oppression, identity politics expanded the scope to include other forms of social hierarchy and power dynamics. The adaptation of Marxist ideas to identity politics involved recognizing that the capitalist system also perpetuates other forms of inequality, beyond class, which are interlinked and mutually reinforcing.

The adaptation of Communism, particularly in its Marxist and Maoist forms, to Western values in the 20th century was a complex process that involved the fusion of these ideologies with existing cultural and intellectual traditions. Marxist ideas were integrated into Western academia, influencing a wide range of disciplines and shaping critical scholarship.

The influence of Maoism inspired more radical elements within Western intellectual and social movements, particularly in the context of student activism and revolutionary politics.

The Combahee River Collective

A Black feminist lesbian organization active in the 1970s, The Combahee River Collective’s historic statement argued that the liberation of Black women required addressing multiple forms of oppression simultaneously, including race, gender, class, and sexuality. One of the earliest articulations of what would later be known as intersectionality, this statement represents a significant adaptation of Marxism to Western values by integrating a critique of capitalism with a focus on identity and intersectionality, recognizing that different forms of oppression are interconnected.

Intersectionality

A concept developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw in the late 1980s, the roots of Intersectionality can be traced back to earlier feminist and Black radical thought, including the work of the Combahee River Collective. Intersectionality examines how different social identities (e.g., race, gender, class) intersect to create unique modes of oppression and privilege. Building on Marxist ideas about social structures and power, Intersectionality addresses the complexities of identity in a way that is more applicable to Western societies with diverse populations.

The influence of Marxism and Maoism on Western society extended beyond academia, impacting social movements, political discourse, and cultural production. By adapting these ideologies to address the specific concerns of Western societies, intellectuals and activists were able to apply Communist analysis to issues like race, gender, and identity, having a profound impact on Western intellectual traditions and social movements and leaving a lasting legacy that continues to influence contemporary debates about power, inequality, and social justice.

Relevant Figures and Organizations

Karl Marx and Marxism:

Marxism provides the foundational framework for much of the 20th-century intellectual movements mentioned in your list. Karl Marx’s theories about class struggle, historical materialism, and the critique of capitalism have been adapted in various ways to address different social and cultural contexts within Western societies. While Marx's focus was primarily on class and economic relations, later thinkers and movements expanded his ideas to address issues of race, gender, sexuality, and identity.

Mao Zedong:

Mao adapted Marxist-Leninist theory to the context of China, focusing on the peasantry as the revolutionary class rather than the industrial proletariat. Maoism introduced ideas of continuous revolution and guerrilla warfare, which influenced various radical movements in the West, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. Mao’s ideas found resonance in Western academia and among leftist movements that sought to address forms of oppression not strictly tied to class but also related to race, gender, and imperialism.

Herbert Marcuse:

Marcuse was a key figure in the Frankfurt School and a prominent Marxist philosopher. He played a significant role in adapting Marxism to the Western context by combining it with psychoanalysis and existentialism. His work, especially in One-Dimensional Man and the concept of “repressive tolerance,” influenced the New Left and student movements in the 1960s. Marcuse's ideas provided a bridge between traditional Marxism and the emerging concerns of social movements focused on race, gender, and sexual liberation, thus contributing to the broader adaptation of Marxism to Western cultural values.

Angela Davis:

Davis is an activist and scholar who has been deeply influenced by both Marxism and the Black radical tradition. A student of Herbert Marcuse, Davis applied Marxist theory to issues of race, gender, and incarceration. Her work connects the struggle against capitalism with the struggle against racial and gender oppression. Davis became a prominent figure in the feminist and civil rights movements, contributing to the intersection of Marxist theory with identity politics and the development of a more inclusive critique of social injustice.

Feminism:

Particularly in its second-wave and later forms, Feminism intersected with Marxism in critiquing patriarchy as a system of power analogous to capitalism. Socialist feminism, in particular, sought to combine Marxist analysis with feminist concerns, arguing that women's liberation was intrinsically tied to the overthrow of capitalist exploitation. The integration of Marxism with feminist theory helped to expand the Marxist critique to include gender oppression as a central concern.

Lesbianism:

Within the feminist movement, particularly during the second wave, Lesbianism was both a personal and political stance that challenged heteronormative structures and the patriarchy. Lesbian feminists argued that both capitalism and patriarchy were interconnected systems of oppression that marginalized and exploited women, especially those who did not conform to heterosexual norms. This perspective dovetailed with Marxist critiques of the family as an institution that reinforces capitalist and patriarchal norms, leading to a broader understanding of oppression that included sexual orientation.

These individuals, organizations, and political movements are connected through their shared effort to adapt Marxist ideas to the specific social and cultural contexts of Western societies. Marxism provided the foundational critique of capitalism and power structures, while Maoism offered strategies for revolutionary change that resonated with Western radicals. Figures like Herbert Marcuse and movements like the Combahee River Collective extended this critique to include a broader range of social issues, including race, gender, and sexuality.

Herbert Marcuse and Angela Davis are directly connected through Marcuse's influence on Davis during her academic career. Marcuse’s ideas about repressive tolerance and one-dimensional society provided a framework for Davis’s activism and scholarship, which integrated Marxist theory with the struggles for Black liberation and gender equality.

The Combahee River Collective built on the intersectional approach that would later be formalized by Kimberlé Crenshaw. The Collective’s insistence on addressing multiple forms of oppression simultaneously laid the groundwork for the development of Critical Race Theory and Intersectionality as tools for analyzing complex social dynamics.

Critical Theory from the Frankfurt School, particularly through Marcuse, influenced the development of various forms of identity politics, as it provided a method for critiquing power that could be applied to different forms of social hierarchy beyond class.

Feminism and Lesbianism within the radical movements of the 1960s and 1970s often intersected with Marxist critiques of patriarchy and capitalism. This intersection is evident in the works of feminist theorists who sought to integrate a critique of gender with a broader analysis of social oppression.

Critical Race Theory and Intersectionality represent a further adaptation of Marxism by addressing the ways in which race, in particular, intersects with class and other social categories to produce complex forms of inequality.

In summary, these connections demonstrate how Marxist theory has been adapted and expanded in the Western intellectual tradition to address the multifaceted nature of oppression, encompassing not just class but also race, gender, sexuality, and identity. This adaptation has allowed for a more comprehensive critique of Western societies and has influenced both academic discourse and social activism.

Links:

Langbert’s original study report

Citations:

Abrams, Samuel J. "There Are Conservative Professors. Just Not in These States." New York Times, July 1, 2016.

Breneman, David W. "Are We Losing Our Liberal Arts Colleges?" AAHE Bulletin 43, no. 2 (1990): 3-6.

Crawford, Jarret T., and Lee Jussim, eds. The Politics of Social Psychology. New York: Routledge, 2018.

Langbert, Mitchell. "Homogenous: The Political Affiliations of Elite Liberal Arts College Faculty." Academic Questions 31, no. 2 (2018): 186-197.

O’Neil, Tyler. “Democrats Outnumber Republicans 70 to 1 in College Religion Departments, 10 to 1 Overall.” pjmedia.com, May 4, 2018. https://pjmedia.com/culture/tyler-o-neil/2018/05/04/democrats-outnumber-republicans-70-to-1-in-college-religion-departments-10-to-1-overall-n171956.

Rojas, Fabio. From Black Power to Black Studies: How a Radical Social Movement Became an Academic Discipline. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007.

Yancey, George. Compromising Scholarship: Religious and Political Bias in American Higher Education. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2017.

For a free Bible and tracts (available to ship in the U.S.A. only) please email us

Download the Armor of Truth Mobile App Free

Armor of Truth, Inc is a 501(c)(3) Non Profit Organization

Donations are tax deductible

By supporting Armor of Truth you are helping to reach thousands of people daily with the Gospel of Jesus Christ and encouragement to persevere in a world that is hostile to the gospel. Please consider making a donation to help support this mission.

Support Armor of Truth, official donation page: Donate

CashApp $aotmin